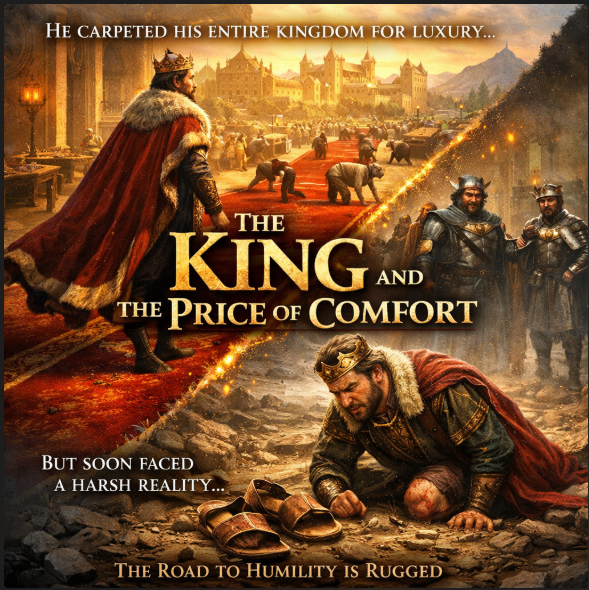

King Aldric of Valmere believed himself to be the most powerful ruler in the known world. His banners flew across fertile plains, his armies were unmatched, and his castle rose from the mountains like a crown of stone. Servants whispered when he passed. Ministers bowed low enough to ache. No one questioned him — not twice.

He also believed something else: that discomfort was an insult.

One bright morning, sunlight spilled through the tall stained-glass windows of the castle’s eastern hall. Aldric walked with his usual proud stride, silk robe trailing behind him, advisors hurrying to keep pace. The marble floor gleamed. Musicians played softly from the balcony above.

Then it happened.

A small, sharp pebble — likely carried in by a worker’s boot — rested unnoticed on the polished floor.

The king’s bare foot came down on it.

He cried out and stumbled. The music stopped mid-note. Advisors froze. Guards rushed forward, thinking he had been attacked.

Aldric lifted his foot, face red with pain and fury. A thin line of blood showed where the stone had pierced the skin.

“What is this negligence?” he thundered. “My own hall wounds me?”

No one answered. No one dared.

The trembling floor steward was dragged forward. He tried to explain — repairs, deliveries, traffic — but fear swallowed his words.

The king didn’t want reasons. He wanted certainty.

“From this day on,” Aldric declared, voice echoing through the chamber, “no hard ground shall ever touch my feet again. Cover the floors of the castle with the softest carpets. No — not just the castle. The roads. The markets. Every walking surface in my kingdom.”

The court gasped.

His chief treasurer stepped forward carefully. “Your Majesty… to cover the entire kingdom would cost more gold than three years of harvests.”

Aldric stared at him. “Then we will spend four.”

“My lord, it may also take—”

“Do it.”

The order was sealed.

And so began the Great Covering.

Carpet makers were summoned from every province. Looms worked day and night. Sheep were slaughtered for wool faster than they could be bred. Trade wagons once filled with grain now carried rolled fabric. Taxes were raised to fund the effort. Farmers left fields to lay padding on roads. Merchants complained quietly — then stopped complaining at all when tax collectors arrived with soldiers.

At first, it seemed glorious.

Rich red and gold carpets lined the palace corridors. Thick blue runners stretched across main streets. Visitors marveled at the softness beneath their boots. The king smiled each time he walked, feeling only luxury underfoot.

But beneath the beauty, strain spread.

Village roads grew muddy under damp carpets. Mold formed. Replacement costs rose. Hospitals reported more illness from overworked laborers. Border patrols weakened because troops were reassigned to transport materials. The treasury began to echo when coins were counted.

Still, no one told the king. Reports were softened before reaching him. Numbers were “adjusted.” Problems were “temporary.”

Months passed.

Then came the invitation.

King Rowan of neighboring Norcrest — a practical ruler known for discipline and sharp wit — invited Aldric for a diplomatic visit and trade discussion. Aldric accepted eagerly. He would show Rowan the superiority of Valmere’s prosperity.

The royal procession traveled in splendor — until they crossed the border.

The carpets ended.

Natural earth began.

Aldric stepped down from his carriage onto rough stone and immediately flinched. The ground felt brutal. Every pebble pressed like a nail. His steps became awkward, then painful. Within minutes, his pace slowed to a shuffle.

Rowan’s welcoming party watched with poorly hidden confusion.

“Is your foot injured?” Rowan asked.

Aldric forced a smile. “Temporary sensitivity.”

They continued toward the city. Gravel roads, uneven steps, and wooden bridges turned the walk into torture. By the time they reached the guest palace, Aldric’s feet were red and swollen. Servants had to support him on both sides.

Word spread quickly.

By evening, the story had traveled through Norcrest:

“The Carpet King cannot walk on ground.”

The next day brought worse.

Rowan insisted on a traditional inspection walk through the military training yard — a sign of mutual respect between rulers. Aldric could not refuse without appearing weak.

He tried.

Halfway across the yard, he cried out and stumbled in front of soldiers, foreign ministers, and visiting traders. He fell to one knee in the dust. A murmur — then laughter — rippled through the watching crowd before officers silenced it.

Rowan helped him stand, but the damage was done. Pity in a rival king’s eyes cut deeper than mockery.

That night at dinner, Aldric overheard servants whispering behind a curtain.

“All that wealth,” one said softly, “and he cannot walk like a farmer.”

He did not sleep.

Instead, he asked for a mirror and looked at himself — truly looked — without crown or ceremony. His feet were bandaged like a patient’s. His pride felt the same.

For the first time, doubt entered his thoughts.

Had he protected himself — or weakened himself?

Upon returning to Valmere, reality no longer hid behind polished reports. The treasury was near empty. Grain reserves were low. Several outer villages had delayed planting season. Carpet rot had ruined entire road sections after the rainy month.

And everywhere he went, he noticed something new:

People walked carefully — not comfortably — afraid to damage what they were forced to maintain.

Comfort had become burden.

He ordered a private walk — alone — beyond the carpeted royal district. The moment his foot touched bare earth again, pain shot upward. He nearly turned back.

But he didn’t.

He kept walking.

Each step hurt. Each step also taught.

By the time he returned, dirty and limping, he had made his decision.

The next morning, he stood before the full court — no musicians, no banners — and spoke quietly:

“My command was foolish.”

No one moved. Kings did not say such things.

“I tried to change the ground beneath everyone… instead of strengthening what carries me across it.”

He held up a simple pair of leather sandals crafted overnight by a village cobbler.

“These cost less than a single hallway carpet.”

He canceled the Great Covering. Resources were redirected to farms, roads, and medicine. Taxes were reduced for affected villages. Carpet makers were paid and reassigned to trade goods. Publicly — and painfully — he thanked the treasurer who had warned him.

Some still mocked him behind his back.

But fewer each year.

Aldric trained his feet again — walking rough paths daily until the pain faded. He visited Norcrest once more, this time arriving on horseback and walking the full stone road beside King Rowan without assistance.

Rowan noticed.

“You walk well now,” Rowan said.

Aldric nodded. “The ground did not change. I did.”

And that became the line remembered longer than his mistake.

Because the humiliation of a king lasted a season —

but the lesson lasted generations.